© John Clarke 2014-

John Clarke

Historian of Brookwood Cemetery

The Aberdeen Granite Industry

Published material on the masonry industry is quite scarce. Therefore when I came across the following account I thought it would be of wider interest, not least given the number of significant granite memorials that can be found at Brookwood.

A 7-

ALTHOUGH Aberdeen is universally known as the Granite City, comparatively little is heard of how the glistening masses of stone are torn from their beds in the bowels of the earth, and cut and hewn into magnificent monuments and graceful colonnades or cornices for the embellishment of our public buildings. One can readily understand how a tolerably soft material like sandstone is wrought into delicate tracery for the beautifying of a cathedral window, but it seems difficult to realise that a material so hard as granite can be cut into sections like a Dutch cheese, and carved into a Corinthian column, a delicately draped figure, or a garland of flowers. Nevertheless, this is done. It is true the labour involved in carving a block of granite is much greater than that required for working freestone, but the result is a hundred times more lasting. Ruskin, wielding a master pen, wrote of the many-

Within recent years an enormous development has taken place in the Aberdeen granite industry, owing principally to the introduction of improved means for quarrying and working the material. Machinery for cutting granite has undergone a complete revolution, and no architectural or monumental detail is considered too elaborate for reproduction in this material. To those unconnected with the industry there are, broadly speaking, only two distinct varieties of granite, grey and red, but in reality, of each of these there is a multitude of tints and sizes of grain, according to the quarry, or particular part of a quarry, from which the stone is obtained. The greys vary from a deep blue to a silvery tint, and the reds from a rich carmine to a salmon pink. Of the original formation of granite the most generally accepted theory is that the rock, with its constituents of felspar, quartz, and mica was heaved up through the earth from a great depth, molten and impregnated with vapour, and the cooling process being slow gave time for its various parts to resolve themselves into the distinct grains which make the stone so beautiful. In Aberdeenshire the principal grey granite quarries are Rubislaw, on the outskirts of the city, and of which most of it is built; Kemnay, which furnishes excellent material for finely-

RUBISLAW GRANITE QUARRY, ABERDEEN.

The granite industry of Aberdeenshire employs altogether about 9,000 men, including quarriers, paving-

Although good rock is sometimes found quite close to the surface of the ground, the best quality of granite is, as a rule, at a fair depth. In appearance a large granite quarry is not unlike the crater of an extinct volcano, except for the busy scene within, the men looking like pigmies on a vast “floor” perhaps two hundred feet beneath the ground level. Boulders of fantastic shapes lie scattered about, one huge mass of detached rock, many tons in weight, giving evidence of a successful blast. Square blocks of stone of the sizes required by the builder or monumental sculptor, are detached from the mass by means of drilling a series of holes into which steel wedges are driven and the stone split up.

A steam drill will sink into the rock fully five feet in half an hour, a process which was formerly almost a day’s work for three men. The larger blocks of stone arc raised from the “floor” of the quarry to the surface by powerful steam cranes, while the smaller stones and waste are conveyed to the top by an ingenious contrivance known as a “blondin”. A blondin is an aerial railway, the name, no doubt, being borrowed from the daring rope-

Now, it may be found necessary to cut a six or seven ton block of granite into several slices or sections, to be used as bases or steps for a large pedestal, or perhaps as a recumbent monumental slab. If this be the object in view, the stone is lifted on to a bogey, which is run on rails right underneath the saw. The saw is a sheet of steel from six inches to nine inches’ wide, about a quarter of an inch thick, and a few feet longer than the stone required to be sawn.

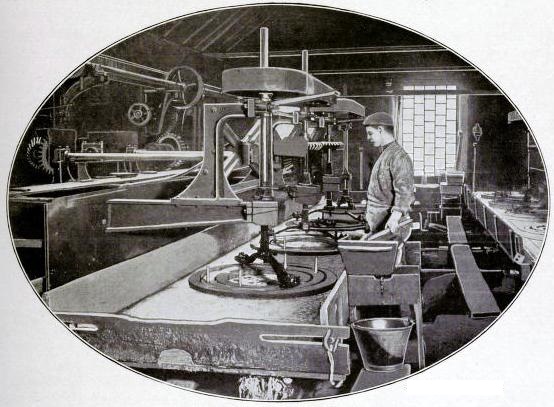

HOW THE GRANITE IS POLISHED.

This huge blade is suspended above the stone with its edge parallel to it, and being swung with a pendulum-

When placed on the polishing carriage, as the machine is called, the granite passes through three distinct stages before acquiring the beautiful gloss so much admired. The first medium used is the shot already referred to, but of a finer grain than that used for sawing. The shot is rubbed over the surface of the stone with revolving metal rings, until smoothness is obtained. Emery powder is then applied, which produces a dull polish. Last of all putty powder is rubbed on with felt attached to the revolving rings, and the polishing process is complete. A bed of granite 23 feet in length will be finished in two days To polish mouldings, iron plates are made to fit the curves of the stone, and the process is carried out with the mediums described, but applied to the mouldings by a machine called a pendulum, the action of which is explained by its name. Columns and urns are made to revolve on lathes, and the gritty substances being applied with the irons and felt, they, as it were, polish themselves. When it is necessary to polish work carved in relief, as is almost invariably the case with orders received from French architects, men known as hand-

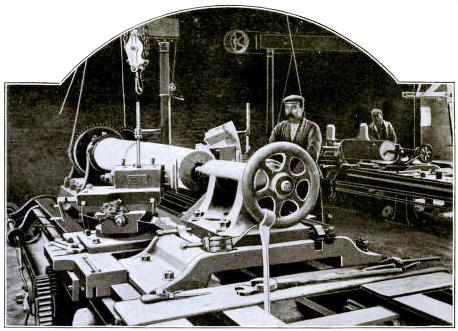

TURNING A GRANITE COLUMN.

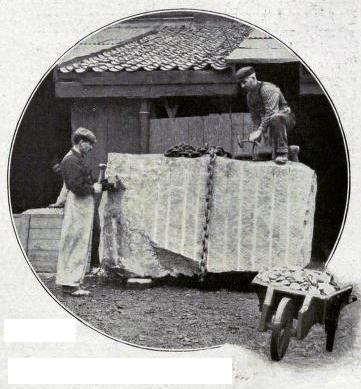

The carving of Aberdeen granite was revolutionised a few years ago by the introduction of the pneumatic tool. The pneumatic tool had been in use for a considerable time in England for caulking purposes, but the people of the United States were the first to apply it to granite, the pioneers of this idea being, it is asserted, Scottish-

In order to make this article complete it is necessary to say a word about the turning of the large granite columns which are a feature of so many of our public buildings. A square stone of the necessary dimensions is procured from the quarry as already described, and in the stone-

PNEUMATIC CARVING TOOLS BEING APPLIED TO A CELTIC CROSS OF GREY GRANITE. THIS STONE IS OVER 17 FEET IN LENGTH.

Aberdeen granite work is exported to almost every part of the globe, although within the last twenty years or so the almost prohibitive tariff imposed by the United States government has considerably diminished the trade with that country. On the other hand, however, there is a rapidly increasing business being done with the Australasian colonies, and also with South Africa, and there is every reason to expect that in the latter country there will be a still greater increase of trade.

One feature of somewhat melancholy interest, in connection with the Aberdeen granite industry, is the large number of military monuments which have been despatched to South Africa, amongst them being those placed over the graves of Prince Christian Victor, General Woodgate, and gallant Dick-

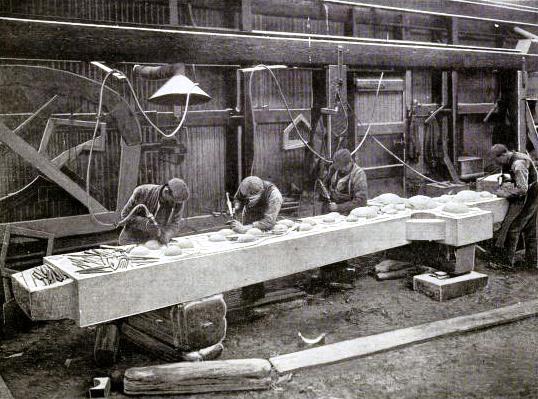

In addition to the trade in the British colonies, there has been a steadily increasing demand on the Continent for polished Aberdeen granite; France, perhaps, being the best customer. French architects seem to prefer the red granites, and some magnificent sarcophagi in this material have been despatched. An interesting example of a French monument is that to Charles Gamier, the famous architect of the Paris Opera House. The whole of the granite work of this memorial was executed in the yard of Messrs. Alex. Macdonald and Company, Limited, the pioneers of polished Aberdeen granite. It is scarcely necessary to speak of the home trade. Everyone in this country has seen some bank, assurance office, or other public building embellished with the product of the granite city, its shining surface defying the grime and smoke of a London atmosphere. Within the last ten years or more, such has been the demand for architectural granite work, that the Aberdeenshire quarries, extensive as they are, have not been able to furnish a sufficient supply, and although it may appear very like the proverbial carrying of coals to Newcastle, it is nevertheless a fact that large quantities of foreign granite are imported into Aberdeen, in the rough state, principally from Russia, Norway, and Sweden. None of the foreign material, however, can compare with the home article. As the deposits of native rock are practically inexhaustible, and the development of the quarrying industry is going steadily on, it is confidently anticipated that in a few years there will be a large enough output of Aberdeen granite to meet all demands.

Apart from architectural and monumental work, Aberdeen granite is rapidly asserting its superiority as a bridge-

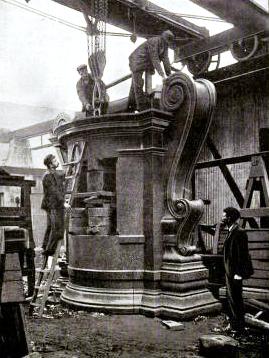

SETTING UP A GRANITE MONUMENT.

(This appears to be the monument to Charles Garnier, architect of the Paris Opera House.)

From Britain at Work: A Pictorial History of Our National Industries. Cassell and Company, (1902).