© John Clarke 2014-

John Clarke

Historian of Brookwood Cemetery

Edith Thompson

The following is an article on the case, written by Professor René Weis for publication in the Times to mark the 70th anniversary of Mrs. Thompson's execution in 1993. It is reproduced here with his permission.

"Edith Thompson was innocent of murder. Her sentence was unjust. Her name must be cleared."

"Edith Thompson was innocent of murder. Her sentence was unjust. Her name must be cleared."

On 9th January 1923, Edith Thompson and Frederick Bywaters were hanged in London, she at Holloway, and he at Pentonville. They were both found guilty of her husband's murder in a quiet street in Ilford one late night in October 1922. Edith was 29 when she died, her lover only 20. The Crown “proved” at the trial at the Old Bailey that although it was Bywaters who stabbed the 32 year old Percy Thompson to death, Edith had set it up. She must have masterminded it because she was a successful business-

But there was no colourable evidence to connect Edith Thompson to the crime. Instead, there was a rash and fanciful wish, repeatedly expressed in her many letters to Bywaters, to be rid of her husband. From such references the Crown inferred poison, and exhumed Thompson’s body. However, the two most distinguished pathologists in the country independently concluded that there had been no attempt at poisoning.

If the “Messalina of Ilford”, as the popular press dubbed her, could not be found guilty of poisoning, then she had to be found guilty of aiding and abetting the murder. Accordingly the Solicitor General scandalously misled the jury when he stated that Edith Thompson’s correspondence contained the “undoubted evidence” of a “preconcerted meeting between Mrs. Thompson and Bywaters at the place” -

The judge failed to set the records straight in a summing up that was notoriously unfair to Mrs. Thompson. During the trial he scribbled on his note pad “great love ... nonsense. Great and wholesome disgust.” The judge could, and should, have told the jury the reason why parts of Edith Thompson’s correspondence were withheld: her letters were deemed too explicit about “women’s things” such as her periods (or lack of them), her two pregnancies (resulting in one abortion and one miscarriage) and, yes, a sexual climax in Bywater’s arms al fresco in Wanstead Park. This was the sort of thing that might have happened to Hollywood starlets, but not to restless British housewives.

Edith Thompson paid a terrible price for daring to be ruled by her passions, and for behaving out of her social class. If confirmation were needed that it was her perceived immorality that brought her to perdition, it is provided by the foreman of her jury. “It was my duty to read them [the letters] to the members of the jury ... ‘Nauseous’ is hardly strong enough to describe their contents ... Mrs. Thompson’s letters were her own condemnation.”

Edith’s famous letters were not at all about sex, or her loathing for her husband. In fact, the bulk of them chronicled her daily life and fantasies for her lover’s benefit, to keep him involved in her suburban routines while he was sailing the oceans of the world. Edith’s natural gift for written expression allowed her to articulate her feelings with remarkable fluency. She devoured books, and substantial parts of her correspondence consist of discussions of sentimental and risqué novels, such as Bella Donna by Robert Hichens. She was the Madame Bovary of North-

A million people signed the petition for the reprieve of Edith Thompson and Freddy Bywaters, particularly for his sake, as he had become something of a hero during the trial for his loyalty to her. His last words to his mother the day before he died, as she left the death cell at Pentonville, were “give my love to Edie”. Bywaters died fearless, Edith Thompson disintegrated on the gallows. Rumours about the circumstances surrounding her death began to circulate at once, giving reason to suspect that she may have been pregnant, and that the observations about her “insides falling out” was a euphemism for a miscarriage. It certainly seems odd that her weight increased dramatically from 119 to 133 pounds between the day she was sentenced to death, 11 December 1922, and the day she died, 9 January 1923, even though she ate very little during her last two weeks in prison, and next to nothing during the four days before her death.

Edith Thompson continues to exercise imaginations, and above all consciences. Occasionally I return to East Ham and Ilford, mostly to show friends where Edith Thompson grew up, her school, the church she was married in, her house in Ilford, the parks nearby, the station through which she commuted, even her bank. She was a truly ordinary woman. The gulf between the legal cataclysm that destroyed her and her own sense of position is best revealed by her reaction to the sentence. As her family entered her cell in the bowels of the Old Bailey immediately after the verdict, Edith rushed towards her father, crying “Take me home, Dad!”, as if he could.

One cannot avoid feeling that a wider and sinister logic operated against Edith Thompson: her husband was dead, her killer would die, and this woman needed to atone for the loss of the two men. She became the first woman in sixteen years to be hanged in Britain. Edith Thompson was innocent of murder. Her sentence was unjust. Her name must be cleared.

René Weis

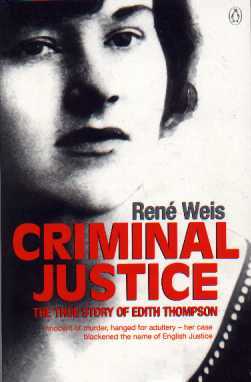

René Weis Criminal Justice: the True Story of Edith Thompson (Hamish Hamilton, 1988; re-

Another Life, a film based on the life of Edith Thompson, was on general release from 15 June 2001 and released by Winchester Films.

You can read a contemporary account of the trial edited by Filson Young Trial of Frederick Bywaters and Edith Thompson (London: Butterworth, 1923).

You can read an account of the special service to dedicate the permanent memorial to Edith Thompson and others.

On 22 November 2018, Edith Thompson was reburied in the grave of her parents in the City of London Cemetery. You can read an account here.